Solid

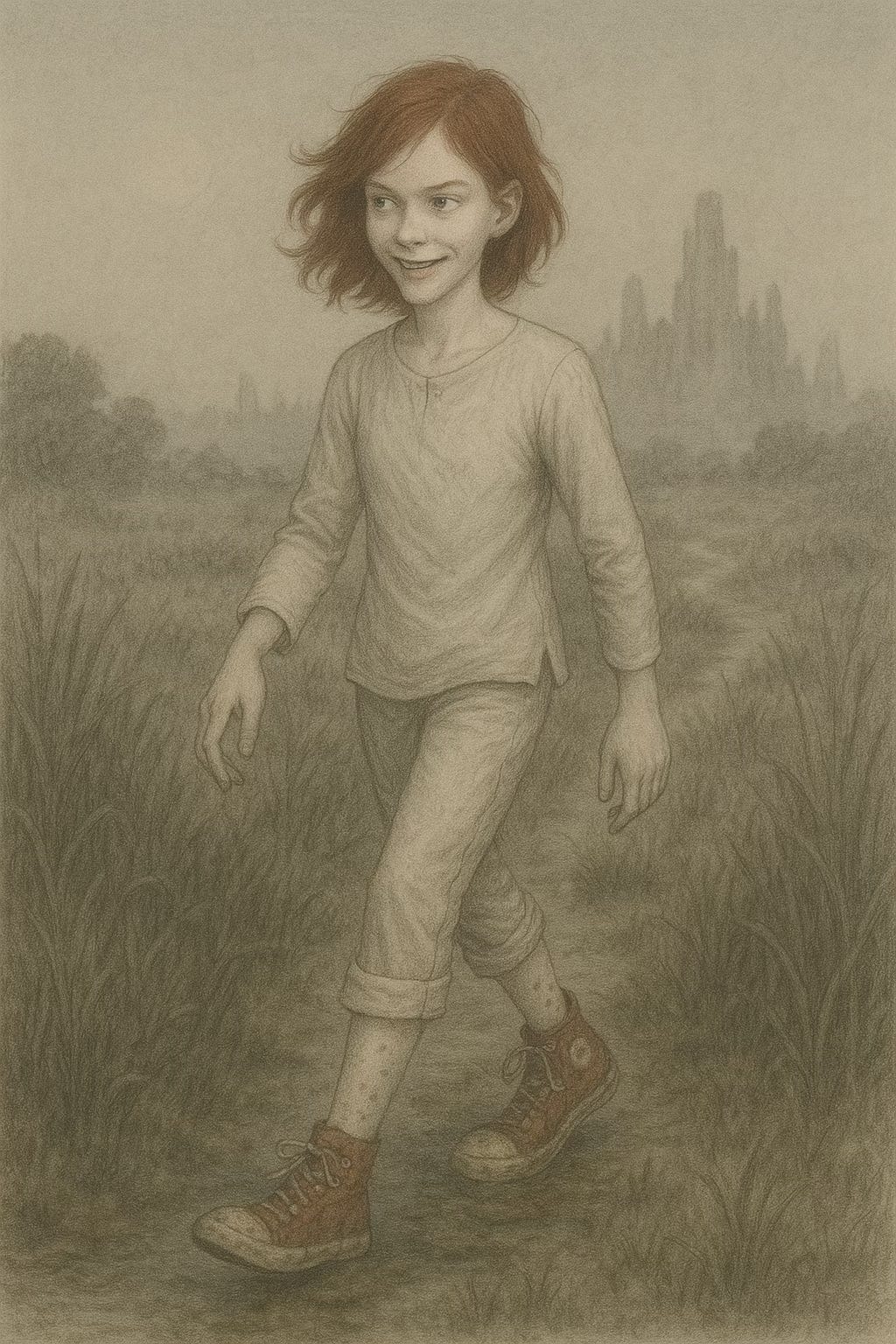

Follow dystopian heroine Chapel Panic on her way to school.

Solid

by Shawn K. Inlow

Chapter 1

Chapel Panic walked out of the L.A. marshes on her way to school. She always cut through a corner of the swamps every gray morning. The green and the wet gave comfort to her where most would find the place grotesque or dangerous, which it was. The pathways here were made by her feet or those of some of the larger animals.

The bile of what was left of the city seeped into the vast tidal marsh, transforming it. Radicalizing it.

The path she walked was beaten down from her twice a day walking. The black waters were receding among the tall grasses and the neon colored oddfrogs were plopping out of sight as she padded along toward what remained of school.

The marsh extended for miles in a great, fetid, estuarial square, bound on two sides by the hard lines of the city above sea level and two sides that had always, in her lifetime, been flooded. To the east, the city was etched on the horizon like faint grey mountain ranges. To the west, the city crumbled slowly into the haze of the sea. Besides Chapel, the only intruders on the marshes were DynaCorp hydrogeologists. She observed them from time to time - studying them as she might anything in the swamp - quietly and from a safe distance. They wore protective clothing and left monitoring devices.

Chapel, by contrast, rustled along in her schoolgirl clothes. Her shirt and pants were both of the light, breathable and drab Cylex. Her pants were rolled up to the knee against the travails of the marsh exposing slight white spindles that ended in the bright red of her old fashioned sneakers. Uncle Marty had given them to her. For whatever reason, he called them "Chucks."

Now churning uphill, Chapel rose to a dry patch of earth and was in sight of a walkway. In short order she stepped onto what appeared to be a moving sidewalk. She skipped onto it and was being whisked along to her destination. At the first junction, the walk slowed and Chapel danced onto another walkway and was soon speeding off in another direction. The walkway began to arch upwards like a rollercoaster above the tangle of the city below and Chapel, impetuous, began to run.

She felt superhuman as she sprinted along the walkway and the air whipped against her face, her viridian eyes squinting above her wide grin.

A red safety message emerged under her feet, "No Running." Chapple scoffed. The air constricted inside the tube and she felt a draft from behind. At the crest, her speed, running on a moving surface, made her stomach sink as she was suddenly airborne briefly as the walkway leveled and sank gently away. Her flying blood-red hair grazed the translucent ceiling and her "Chucks" peddled slowly on air. It was like flying.

Chapel had always thought her hair to be brownish, but Uncle Marty proved to her it was, indeed, red.

"It's the color of blood," said Marty one day at the shop, "When it dries."

This had fascinated Chapel, so she pricked her index fingers with her good knife and smeared them across her cheeks, just below her eyes. The mirror had shown her face to be a strange composition on albino skin as she waited for the smears to dry. And, like usual, Marty was right. Blood starts out crimson, she decided, but it deepens as it dies down to almost a brown rust color.

She landed taking big, leaping steps, to avoid sprawling on her face and coasted to a cool and graceful stop where another junction came into view.

There were designer children, corporates, on this footpath. Had they been on the path by the marshes, she might have recklessly bowled them all over.

These new commuters were not walking. They were leaning forward and being carried along by the movement of the path. Chapel, impatient, looked to be gracefully dancing at speed between them and out of sight of their disparaging stares.

A boy stepped aside from Chapel as the tousled wild thing blurred by in a streak of red. He, antiseptically clean, caught the smell of sweat from her and the earthy smell of mud spattered shoes and legs.

"Freak," he thought.

Chapel felt all the stares. She didn't know whether the slight, good looking boy’s face was registering disdain or surprise. Whichever, she thought, the Nancy-boy had better keep his lip shut or she'd fatten it for him. That's what Uncle Marty called the kids who were being set up for government jobs. Nancy-boys. Marty always said in the old days softies like that couldn't even step on the playground.

Playground.

The walkways merged and merged again until Chapel was amid a throng of children on their way to DC #17. She tip-toed off the walkway to a large plaza which channeled students like spectators into a stadium.

Passing through turnstiles, she knew she was being scanned and she closed her eyes. The others seemed either to not care or not know that they were being searched and identified. Both the idea of being searched and of being present and accounted for at school dimly bothered Chapel. She had always vowed they would never look in her dark blue-green eyes. Uncle Marty, always full of truisms, said the eyes were the window to the soul. So Chapel didn't mind so much them knowing her identity as much as them knowing who she was inside.

School #17 was a massive thing built on the bones of several old schools. Chapel knew only one teacher and few classmates. The only adults, besides Mr. Hurtado, that appeared were maintenance people in Dyna-Corp outfits.

The flood of children moved down wide halls past an immense section of administrative offices and into the well of an auditorium. Each student filtered to the seat with their corresponding number. Each seat was a comfortable affair with a pull down screen upon which interactive lessons played out.

At the dais in the center front of the auditorium stood Hurtado. He was a thin, well dressed, Latino man and he was the only teacher in a classroom of 12,000.

The youngest students sat closest to the dais. The oldest sat furthest away and matriculated out the top of the auditorium. Just over half way up, Hurtado saw the familiar bouncing ball of red hair on her way to her seat.

He entered her number on a keypad and her biographical information came onto the screen. Looking down as he loaded the day's history lessons he noted how she stood out in the crowd. She even walked differently than the others, in a kind of baroque, shifting way that looked aimless, haphazard. And that strange color of red hair was not one they would ever think to engineer.

She was a born. One of the children who were conceived and born the old fashioned way with all the attendant asterisks. There were many of them in society and Hurtado could look around the auditorium and select them easily enough by sight. They were a significant minority, though, and this one, Hurtado thought, was different by an order of magnitude even from other borns.

He liked the way she attacked her lessons. In the history module where students gamed out battles in the Spanish Civil War from different sides, she chose not only Governor Francis' role, but also that of the famed local rebel, Chaves. It was clear that young Ms. Panic received the corporate lesson like a prize-fighter.

The school would have a detailed list of borns and certain administrators made their living at keeping keen track of their progress. Hurtado made notes on Chapel, too, and mostly kept them to himself.

Borns, statistically, tended to grow into dissidents. They were agitators who stubbornly persisted in asking nagging questions of the company and its officials. Officially, they were free persons living inside the safe corporate zones. Unofficially, they were red-flagged and they needed to be watched. Borns sometimes became terrorists at about the same time their questions became unavoidably inconvenient.

Chapel Panic, Hurtado thought, had no idea how difficult a path her life would take.

Hurtado knew the difficulty first hand. He had been what used to be called an illegal in a country his forebears had once called home, but his impeccable paperwork and diction transformed him officially into a U.S. born ... an educator even.

He was the perfect company man. He knew people even in an age where few met in person and fewer looked you in the eye. He could read a bureaucrat even in a teleconference. Even in the syntax of a memorandum. Hurtado could see which way the wind blew - officially and unofficially. He seemed always to know the truth and then an extra measure of the truth.

It was this set of skills that insured Hurtado and ensured he would be the last teacher standing at DC #17. He remembered his farewells ten years ago with Stan Polonko.

Stan was senior to Ed and DynaCorp was downsizing the staff again. The teachers' contract called for another increase and the district could only afford one teacher over the next three years on the smallest of budgets. One of them had to go.

The two stood leaning against their cars in the teachers' lot; a lot with only ten spaces.

"I don't know how you do it, Ed. Keeping up with all the new regs and making sense of all the stats they need. Its just too much."

Hurtado smiled. "It's not about absorbing things. It's more like knowing what to filter out," said Hurtado. "And there's a lot of nonsense. Most of it is nonsense."

Stan laughed, leaning on the fender of his car. Ed knew that the secret to staying with the system was not being interested in the details of the teaching, but in the way that the data flowed. Programs were set for education and they were administered and his job was merely loading the approved information and then simply getting out of the way of the students' outflow of data.

The administration would make whatever meaningful statistics out of the information that they deemed necessary. Countless bureacrats in a massive Dyna-Corp budget for administration made lives out of children's numbers. Hurtado, knowing how the data flowed and to where, was the one instructor School 17 could not do without. He understood it. Not just where the information went, but why.

This was knowledge that made him essential. More essential than Stan, anyway. And it was only the safest of instructors - those who were not inquisitive, those who didn't want to be too involved, who could be trusted anywhere near that kind of data-flow. This, Ed knew, could be translated into power or ruin. The thing was to remain indifferent.

For students, the way they interacted with the educational code meant they would go to work in menial jobs, tech jobs, infrastructure jobs, military jobs, aerospace fields, and on and on.

Students like Chapel, those who were born, had no chance at more than a life on the fringes. She was genetically doomed to failings of all kinds. She could be defective in the head or heart. She might up and croak of an embolism or the early, savage cancers that would eat up borns so often. Statistically this was all true. It was never said. But it was true. True things are always the quiet things.

Still, Chapel was a rare intellect. It would get her nowhere but in trouble one day, but, to Hurtado, this was a data-stream to behold.

In the history sections, she role played the great military leaders of the old U.S as well as their enemies. She had won World War II for both the Axis and the Allies. She had understood the Battle of L.A. so deeply that she could inhabit a general or militiaman as the lesson plan changed with equal aplomb. In fact, her successful trials in Chaves' shoes surely attracted attention somewhere.

It wasn't that she was a military genius. It was more, Hurtado thought, that she understood people. People, genetically groomed or not, all ticked in basically the same way. It was a truth... one of those quiet things... that Ed Hurtado appreciated.

In today's history lesson, he'd locked two students, unbeknownst to each other, on either end of the Southern California Civil War. Chapel Panic was leading the rebellion.

I can't wait to read more about Chapel!